The end of each year is a time for reflection. We often look back on the past year and try to summarize our milestones. Sometimes we set New Year’s resolutions with the best of intentions. At the moment I’m thinking about someone who won’t be part of the new year.

That is the way of things, perhaps the hardest part of being human, knowing almost as soon as cognition forms that there are bookends on all of us. That inescapable awareness is in many ways the essence of our humanity. We have no choice but to internalize it with relative calm. It doesn’t make it easier when we say goodbye, but it does give us a chance to express thanks for the lives around us who change the course of our own.

The Reverend David P. Coon was the head of the school I attended through middle and high school. He officiated at my wedding. I dedicated my second book to him. It is difficult to record in words what he meant to me because I would be looking for the kind of words it takes to summarize five decades of character-building.

Certainly the earliest of those years were more concentrated, but those took place at a time when I was least likely to understand the transformation he was causing to occur in my mindset. In those days he was Father Coon and I would literally tilt my head up to be able to look into his eyes. He walked the halls of our campus with a magnificent physical presence, a baritone voice that reverberated in the corridors, an embodiment of pure confidence, and a sense of authority that never needed to be asserted. He could be questioned on matters of intellectual curiosity, but not on matters of expectation. He expected we would take our education seriously, our shared community seriously, the mandate of maintaining humility seriously, and the place we would come to take in the world seriously.

He was a serious man and he endeavored to help us see the seriousness in the paths before us. He also laughed as loudly as anyone I’ve met and made us laugh, mostly at ourselves at the times our seriousness crossed into counterproductive meandering. We could ponder the world, obsess on this philosopher or that scientist, but we always needed to be moving forward. Laughing at ourselves moved us forward. It helped us frame ambition appropriately in service to others. It was okay to be on a reward path, but it was not okay to think that material rewards meant a hill of beans compared to healing our world. To gain his respect, we would be required to commit our gifts to the continuum of that healing.

I would not be exaggerating to share that without Father Coon’s influence, it is unlikely I would be typing these words. Our teenage years are a crapshoot at best; mine were a casino where the odds were daunting. Somehow this stranger, this teacher of the impossible, got me to stop betting against myself. He mopped up a mess and caused me to believe everything ahead of me was more important than everything behind me. How much of that did I understand? Come on, I was a teenager, none of it. Yet I remember it now, and it works even better with fewer years left ahead of me than there are behind me.

Was he a visionary? He would just say he was a teacher. I’m going to stick with visionary.

His career was remarkable, but I am going to let others write about the expanse of that. He took an all-boys school built on the ancient tradition of recital and transformed it into a modern coeducational place of learning. He initiated change that broadened the paradigm of “sage on the stage” to embrace peer cooperation that put the whole of the student body above the celebration of any single student. One Team, we called it. He elevated ‘Iolani School to global recognition as a laboratory of exemplary process and a trusted model for lasting outcomes.

He took the tragic lessons of the Vietnam War and opened the minds of a diverse audience to the possibility of peace. His sermons beckoned the beauty and unlimited empowerment of embracing one’s opposite. He was a theologian who could preach with the best of them, but he was a pragmatist who knew declarations without substantive action were the fast track to cynicism. He was not a cynic. His faith was unwavering, a boundless reservoir of resilience and optimism, ardently tested, joyously unshakeable.

If you needed food, water, a quiet moment of prayer, or a reinforcing nod of encouragement, you didn’t have to ask. He was always showing us how kindness and strength were compatible. He was an inspirer of unusual aspiration. The highest order of ourselves is of course never achievable, but that didn’t mean he wasn’t going to make it our life’s work to try.

Later in life, when he presumed I had reached adulthood, he insisted I call him Dave. That in his mind was one of the least difficult challenges he presented to me. If only he knew.

My wife, Shelley, there with Dave and a few family attendees at our wedding with a little New Testament and a little Old Testament, likes to talk about planting seeds. This is her spirituality, and she immerses herself in it as a matter of routine. When I mention the five decades of Dave, it is just these seeds that he planted that have blossomed in different expressions over the years. At our wedding, as I broke the glass, this Episcopal priest belted out the words “Mazel Tov” with such resonance they probably echoed in Jerusalem.

Those echoes live in me today. I’ll carry the octaves of his voice with me until my inescapable fate is the same as his, the same as us all. The learning inside me is without end because he made that important to me. The questions in me are more important than the answers because he showed me why the questions are eternal but the answers get rewritten by the centuries. Judgment is for the certain, and how many of us can be that certain with so little knowledge? Reflection takes us forward, always forward, because it requires systemically removing our ignorance. Forward is a path to wisdom, where humility is not a choice, but a necessity.

Demonstration of awe and honor is common among theologians. Dave knew that, likely early in his life, no problem. Would you expect less of a kid who grew up boxing in Flint, Michigan only to become a man of the cloth in Hawaii? The trick wasn’t that he knew it. The trick was he got me to know it, a highly unlikely candidate for that sort of unnerving alchemy.

And the next kid. And the next kid. And the next kid.

Those were the seeds he never stopped planting. They flourish now in every part of our world, across languages and borders, wherever there is a need for healing. The lives he inspired carry forward hope, breathe aspiration, and most of us try to remember on occasion to laugh.

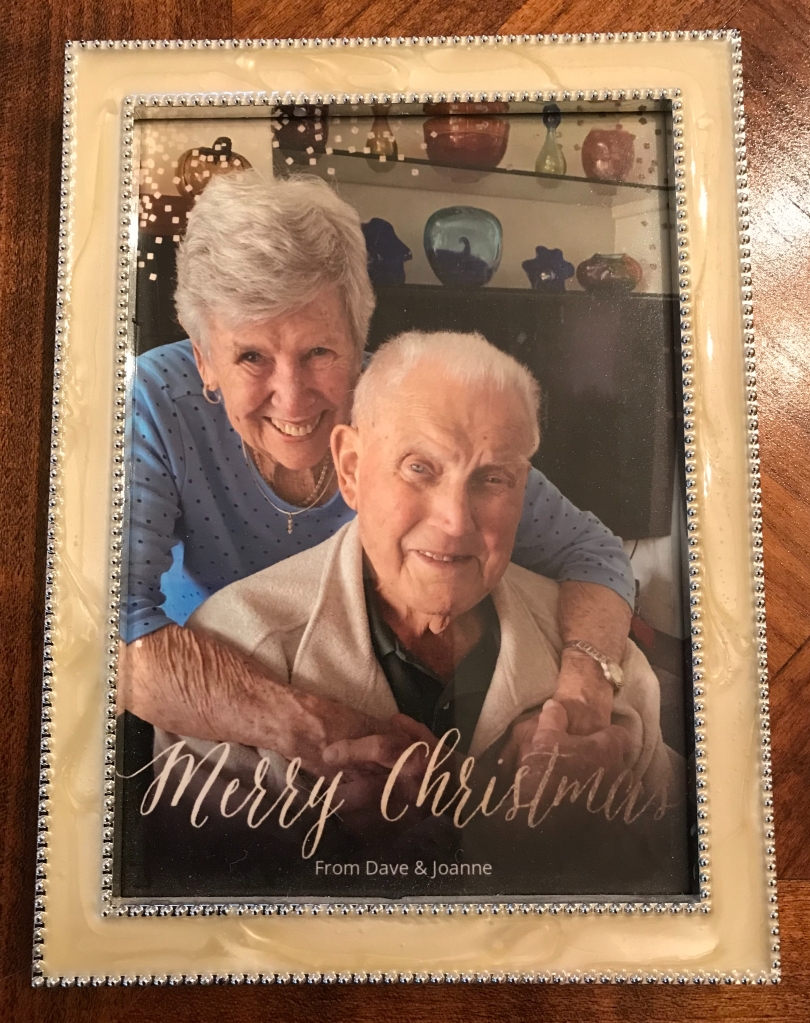

Earlier this month I received our usual Christmas card from Dave and his wife, Joanne. In it was a printed note that said it would be their last, that they were going to spend their remaining time focused on each other and their family. I immediately put our card in the mail to them, telling them I would frame their photo and keep it on my desk forever. That card came back undeliverable. Of course, I didn’t know he was in hospice. That makes this almost our last Christmas together.

I end the year incomplete. Timing is everything and we seldom get to say goodbye to everyone we lose. I enter the new year a little more alone, a little less formed, but in knowledge that those seeds were well-planted if not fully seen and understood a half-century ago. Our character is tested daily, our mistakes are endless, and our learning is forever incomplete. Each of us should be so lucky as to have a few people who guided us forward and never let go. If you enjoy the good fortune to have been so inspired by a person of such wisdom, there aren’t enough ways or words to say thank you. We can only offer a humble appreciation.

Dave, this appreciation is eternal, as are your teachings, as is your incomparable love.

_______________

Image: Dave & Joanne Coon, Christmas Card 2023